A World Not Ours 2017

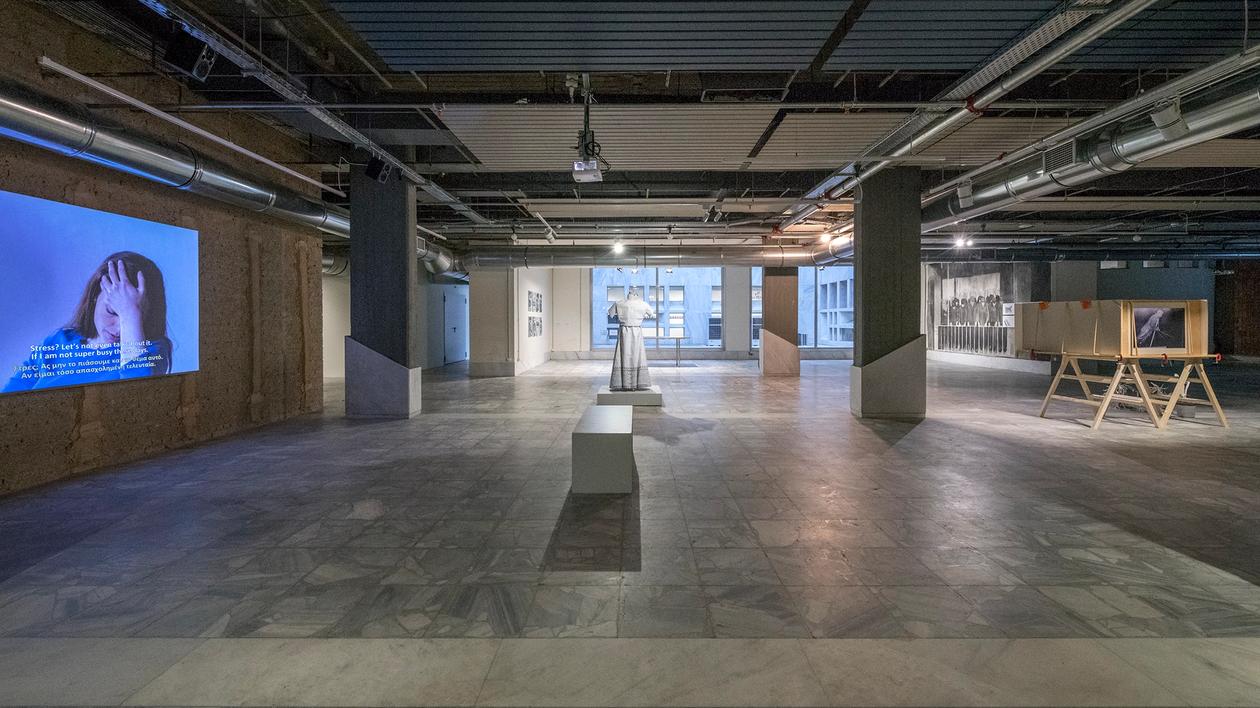

Aslan Gaisumov, Household, 2016 (άποψη εγκατάστασης)

Φωτ.: Sébastien Bozon

Συμμετέχοντες καλλιτέχνες

Curator

A World Not Ours

Text by Katerina Gregos

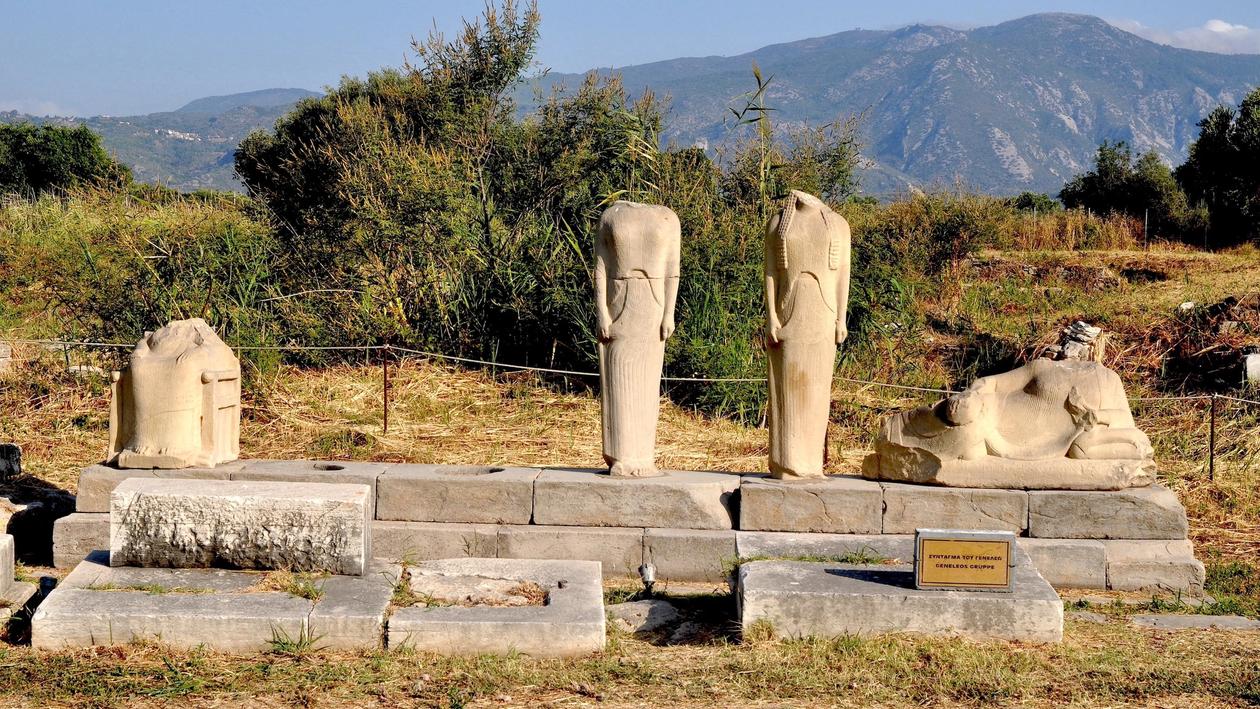

The exhibition began last summer at the Schwarz Foundation’s Art Space Pythagorion, on the island of Samos, Greece, a location that has been at the heart of the refugee crisis that broke out in 2015. Samos was one of four Greek islands alongside Lesbos, Kos and Chios that bore the brunt of this humanitarian crisis, which remains a pressing, unresolved issue for the whole of Europe. The exhibition aims to counteract the standardised, simplified and one-dimensional portrayal of the refugee crisis, which is often reduced to images of rickety boats and the perilous sea crossings from Turkey and Libya, and instead looks into the before and after of this dramatic moment. While the first chapter of the exhibition focused on the experience of flight, the precariousness of the journey, and the clandestine economy that fuels the plight of the refugees, this iteration at La Kunsthalle Mulhouse will extend its focus to what happens once refugees have reached the ‘promised land’ in terms of reception, legal procedures and daily reality, as well as looking into how European citizens experience the migration crisis themselves.

The exhibition also explores problems of the representation of suffering, recalling Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), as well as asking questions about the ‘ownership’ of refugee images and who has the right to represent them. Finally, A World Not Ours aims to provide a counterpoint to the unfortunate opportunism that the refugee crisis has engendered, with some in the so-called ‘art world’ professing their engagement by producing facile one-liners and generating publicity for its own sake. By contrast, the work that is on view is the result of in-depth, long-term research, on-the-ground engagement and first-hand experience. The works here are the result of sincere motivation and hands-on engagement, as opposed to what Tirdad Zolghadr has called ‘poornography’: the use of images of poverty and precariousness to create sensational images in the media as well as in art. This exhibition includes artists who opt for a more nuanced way of working with these highly sensitive issues, who stay under the radar, working with discretion, thoughtfulness and generosity. Most of The exhibition 7 La Kunsthalle Mulhouse the artists here have a proximal and intimate relation to trauma and communal experiences of suffering, and do not have the luxury of a detached touristic viewpoint of the pain of others. They are insiders to trauma, rather than outsiders. Many of them come from the Middle East or South-Eastern Europe, from countries that have experienced war, exodus and perilousness first hand, and thus they also bring an empirical element into their negotiation of the complex issues underlying the representation of the refugee crisis. The city of Mulhouse is a particularly relevant context for this exhibition. Mulhouse has one of France’s highest immigrant populations, and is also a border town at the edges of Germany and Switzerland. All three countries have been at the forefront of the heated debate around immigration, and have witnessed extreme reactions towards it, manifested in toxic right wing populism, for example. A World Not Ours borrows its title from the award-winning eponymous 2012 film by director Mahdi Fleifel, which in turn borrows its name from a book by the Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani (1936–72). The exhibition includes a group of artists, photographers, filmmakers and activists who offer different reactions, reflections, and analyses on the ongoing issue of the refugee crisis in Europe and the complex issues underlying it: from the economic, social and political, to the humanitarian and the personal. Deploying diverse practices from installation, photography, film, video and direct action, the work of the participating artists provides deeper insight into the plight of the refugees and points to the complex roots of one of the most pressing issues of our time, while contextualising it within the larger global picture.

Press

- Anti-utopias, A World Not Ours. Curated by Katerina Gregos (EN)

- Financial Times, Maya Jaggi, A new art show on the frontline of the refugee crisis (EN)

- artnet news, Hili Perlson (Review), On Samos, Greece, a Show Takes an Intimate Look at the Refugee Crisis (EN)

- Monopol, Donna Schons, Die schwindende Macht der Bilder (DE)

- Die Welt, Anne Waak, Ferien für immer (DE)

- FAZ - Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Kolja Reichert, Die Kunst der guten Absichten (DE)

- Tagesspiegel, Bernhard Schulz, Auch Griechen flüchteten nach Samos (DE)

- Kathimerini, Margarita Pournara, Κοιτάζοντας κατάματα την αλήθεια (GR)

- ελculture, Argyro Bozoni, Το Πυθαγόρειο της Σάμου έχει ένα λόγο να υπερηφανεύεται (GR)

- ελculture, Argyro Bozoni, Eκπαιδευτικό Πρόγραμμα στο πλαίσιο της έκθεσης "A World Not Ours" (GR)

- ελculture, Argyro Bozoni,«Πιστεύω ότι αν η τέχνη διδασκότανε στα σχολεία, θα ήμασταν ίσως πιο πολιτισμένοι και λίγο καλύτεροι άνθρωποι» (GR)

- EfSyn, Paris Spinos, Καλλιτέχνες χωρίς σύνορα για το προσφυγικό (GR)

- To Vima, Marilena Astrapellou, Η Σάμος δείχνει τον δρόμο (GR)

- e-flux Announcements, A World Not Ours (EN)

- The Art Newspaper, Emily Sharpe, Welcome to Basel (and Mulhouse) (EN)

- artnet news, Caroline Goldstein, Beyond the Fair: 14 Shows to See While in Switzerland for Art Basel (EN)

- ελculture, Νέα εκδοχή για την έκθεση «A World Not Ours» που ταξιδεύει από το Art Space Pythagorion της Σάμου στη γαλλική πόλη Mulhouse (GR)

- culture now, Η έκθεση A World Not Ours ταξιδεύει στη Γαλλία (GR)

- artlog, Yvonne Ziegler, A World Not Ours (DE)

- kunstaspekte, A World Not Ours (DE)

- Elodie Bernard, A World Not Ours – La Kunsthalle – Mulhouse (FR)

- artshebdomedias, A World Not Ours | Exposition collective (FR)